Going Far, Together

Program manager Arielle Hernandez and lab manager Thad Howard examine test results from Ugandan patients.

Program Takes Expertise in Sickle Cell Treatment to Uganda, Where It Is Sorely Needed

The Laboratory: a storage space in Kampala’s central lab building, transformed in less than two weeks with equipment, supplies and manpower.

The Staff: four newly trained Ugandan employees of the Ministry of Health.

The Goal: to save tens of thousands of Ugandan children from the painful, crippling effects – and often, untimely death – caused by sickle cell disease.

It is all part of The Ugandan Sickle Surveillance Study (US3), a cooperative endeavor between Cincinnati Children’s and the Ugandan Ministry of Health. It started in February 2014 as a way to identify sickle cell in one of the areas of the world most affected by the disease, and least equipped to handle it.

“Sub-Saharan Africa is ground zero for sickle cell,” says Russell Ware, MD, PhD. “It’s where the disease originated, where the gene mutation first occurred, and where most of the patients are.”

Ware, director of the Division of Hematology at Cincinnati Children’s, has been researching sickle cell disease for 30 years. But his efforts had focused on children in the United States − a tremendously worthwhile effort, but not nearly enough. “It’s not addressing the global burden of the disease, he says. “Only 1 percent of the sickle cell patients in the world are born in North America.”

It took several trips to Africa for him to realize how little was being done in a place where the incidence of the disease was so great.

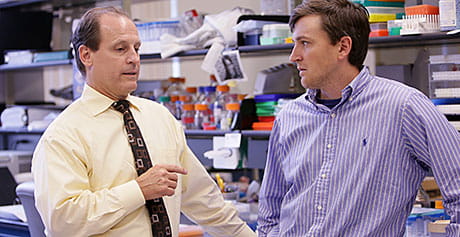

Charles Kiyaga (left), with Dr. Russell Ware, oversees the US3 study in Uganda. The program was designed to be run by the Ugandans; they process some 2,000 tests each week.

Using an Existing Network

Ware did some digging, and learned about the Early Infant Diagnosis (EID) program, begun in Uganda in 2006 by the United Nations to combat high rates of HIV infection in babies. The program established a national network that collects and tests 100,000 blood samples each year from infants born to HIV-infected mothers. Blood spots from standard heel sticks are collected on postcards, then transported from around the country for testing at the Central Public Health Laboratories in the nation’s capital, Kampala.

After analysis for HIV, the samples were thrown away. Ware wondered: why not re-purpose them? “By simply using those same cards to test for sickle cell we could get an idea of the burden and distribution of disease across the country.”

He and his team worked with Ugandan Ministry of Health officials and staff of Makerere University in Kampala to make it happen. The result is the US3 study.

Of the estimated 400,000 babies born in the world each year with sickle cell disease, 300,000 of those births occur in sub-Saharan Africa. There are African countries with higher rates of the disease, but Ware chose Uganda because it was politically stable, safe, and Ugandan officials had a growing awareness of sickle cell’s devastating effects.

Creating a Sustainable Model

Working with staff of the Ugandan Health Ministry, in under two weeks, Ware’s team converted a small storage area in the central lab in Kampala into a fully operational sickle cell testing laboratory. Cincinnati Children’s donated the equipment and testing supplies; Ware’s team helped set things up and conducted the training.

“We started from scratch,” says Arielle Hernandez, the US3 project coordinator. “They didn’t have a sickle cell lab − no capacity, no equipment or training whatsoever. It was just a storage closet.”

Hernandez and Thad Howard, Ware’s research lab manager, worked with the Ministry of Health staff to write a study protocol. They trained four Ugandans to perform the tests and run the lab.

Those technicians now process about 2,000 blood samples each week; the goal is 75,000 to 100,000 within a year. Weekly Skype meetings allow staff on both sides of the world to talk through questions and concerns. Test results are reviewed each week by a team in Uganda as well as by Howard, who says the skill and hard work demonstrated by the Ugandan technicians has been remarkable. “Nobody else is doing this in the world,” he says. “They are quickly becoming the leader in screening.”

Ware says the engagement of the Ugandans is crucial to the study’s goal of turning the tide of sickle cell disease. “When you think about studies overseas, the idea of teaching and sustainability is important. They have learned to do this quickly and well.”

Planning Ahead

After just five months, the US3 study has pinpointed four areas in Uganda where the incidence of sickle cell is highest. Ware and his team are working on next steps for when the surveillance study wraps up next February.

“We have already planned with the Health Ministry to begin a new project to screen all infants born in those four districts,” he says.

The Cincinnati Children’s sickle cell team trained Ugandan Health Ministry staff to run the sickle cell lab in Kampala.

Treatment Is Crucial – and Affordable

Once children are identified as having sickle cell, getting proper treatment to them is the essential next step, says Patrick McGann, MD, a Cincinnati Children’s hematologist who is working with Ware on another study in Africa of treatment for sickle cell.

The two hope to use US3 data to convince government officials and funding organizations of the scope of the sickle cell problem, and the difference treatment can make.

“It doesn’t take expensive medicines to make sickle cell better,” says McGann. “What these babies need are routine vaccinations and prophylactic penicillin. Those two steps will prevent a huge number of deaths. Without that, it is estimated that 50 to 80 percent of the babies will die in the first couple years of life.”

Raymond Bullucks was diagnosed with sickle cell disease as a toddler. His early childhood was an odyssey of medical encounters, including frequent blood transfusions, surgery to remove his gall bladder and pain crises severe enough to require two or three hospital admissions per year.

Raymond Bullucks was diagnosed with sickle cell disease as a toddler. His early childhood was an odyssey of medical encounters, including frequent blood transfusions, surgery to remove his gall bladder and pain crises severe enough to require two or three hospital admissions per year. Sonya Moore has seen how hydroxyurea improved life for her 12-year-old daughter, Shanoah, who was diagnosed with sickle cell disease shortly after birth. “She was in the hospital about three or four times a year and on antibiotics and pain medications around the clock for two or three days at a time,” Sonya says.

Sonya Moore has seen how hydroxyurea improved life for her 12-year-old daughter, Shanoah, who was diagnosed with sickle cell disease shortly after birth. “She was in the hospital about three or four times a year and on antibiotics and pain medications around the clock for two or three days at a time,” Sonya says.