Description of Ventricular Septal Defects

Ventricular septal defects are among the most common congenital heart defects, occurring in 0.1 to 0.4% of all live births. Ventricular septal defects are one of the most common reasons for infants to see a cardiologist (a doctor who treats the heart).

Ventricular septal defects occur in many locations and sizes. The ventricular septum is made up of different types of tissue, with one part composed of muscle and another part made of thinner tissue. The location and size of the hole within the septum will determine in part how to treat the ventricular septal defect.

Small ventricular septal defects rarely cause problems. A doctor usually discovers these holes by noticing an extra heart sound called a murmur on a routine physical exam.

Most of these small holes will close on their own, particularly if they are in the muscular part of the septum. Even if these holes do not close, they will rarely cause any health problems.

However, these holes can sometimes be connected to the development of other heart issues. If the small ventricular septal defect does not close, the child should continue to be seen by a cardiologist for occasional checkups.

Large ventricular septal defects cause symptoms, often developing gradually in the first few months of life. Before birth, the pressure on the right side of the heart is equal to pressure on the left side of the heart.

As soon as a baby takes their first breath, the pressure in the lungs and the right side of the heart starts to decrease. This process is slow and usually takes about 2-4 weeks for the pressure in the lungs to reach normal level.

Therefore, in the first few weeks of life, babies with large ventricular septal defects may show no symptoms. As the pressure in the right side of the heart decreases, more blood will flow to the lungs because this is the path of least resistance (from the left ventricle through the ventricular septal defect to the right ventricle and into the lungs). This will gradually lead to symptoms of congestive heart failure and must be treated.

Medium or moderate ventricular septal defects are more challenging to predict. Sometimes babies born with moderate ventricular septal defects will have problems with congestive heart failure like babies with large ventricular septal defects. Others will have no problems and will need to be watched.

Ventricular septal defects never get bigger and sometimes get smaller or close completely. When a baby is diagnosed with a ventricular septal defect, most cardiologists will not recommend immediate surgery. They will closely watch the baby and try to treat symptoms of congestive heart failure with medicine to allow time to decide if the defect will get smaller or close on its own.

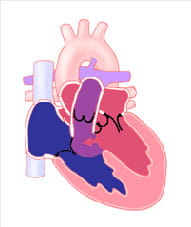

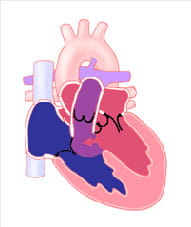

View 2D images of Ventricular Septal Defect.

Learn about the Heartpedia mobile app. The app shows anatomically accurate images of congenital heart defects and repairs of those defects.