After Kidney Transplant

Kids are living longer and better—but it takes constant vigilance

|

“Having younger recipients has taught us what we have to do to make the kidneys work successfully." |

Transplant surgeon Maria Alonso, MD, has been transplanting kidneys for nearly two decades. A lot has improved in that time.

“We know more about organ matching. The nephrology doctors are preparing kids better, getting them to grow with good nutrition. And we’ve learned a lot technically,” she says.

Much of that technical expertise has come from transplanting increasingly tiny infants, Alonso says.

Many of the babies Alonso now transplants would not have made it to birth just a few years ago, or would have died shortly after birth. But advances in fetal medicine have changed that.

|

“Our fetal medicine colleagues can bring babies with congenital urological abnormalities to term with healthier lungs, and we’re being asked to transplant them,” she says. “Having younger recipients has taught us what we have to do to make the kidneys work successfully.”

Working successfully means that, with careful tending, the kidneys continue to function into the child’s adulthood.

“In 30 years, half the kids who receive a living donor kidney today will continue to have a healthy, functioning kidney,” she explains.

Life After Transplant

Helping patients determine what happens during the years after transplant is no easy task, especially for teenage patients, says Jens Goebel, MD, Medical Director of kidney transplantation at Cincinnati Children’s.

“Getting young people to follow the medical regimens required after kidney transplant is an enormous challenge,” he says. In the first year after transplant, kids may take up to a dozen medications a day. Many of those medications can cause weight gain and other changes in physical appearance that are particularly difficult for teenagers.

|

Jens Goebel, MD, and his team have published extensively about the difficulties of getting young transplant patients to comply with treatment. |

Goebel and his team have published extensively about the difficulties of getting young transplant patients to comply with treatment. In one recent article in Pediatric Transplantation, he and Cincinnati Children’s adherence researcher Ahna Pai, PhD, discuss 33 patients coming to Cincinnati Children’s for dialysis; nearly 43 percent had a transplant that failed because they did not take their immunosuppressive medication.

The Risk Of Heart Disease

And there are other obstacles.

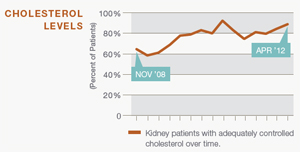

“The biggest long term health challenge for these patients is cardiovascular disease,” says David Hooper, MD, a nephrologist at Cincinnati Children’s. “The risk is about 50 times that of the general population.”

Even though the risk of heart disease for kidney transplant patients is well documented, Hooper says, it has not been a priority in their post-transplant care. The answer seems simple enough — monitor the patients for elevated blood pressure and cholesterol. But it hasn’t happened.

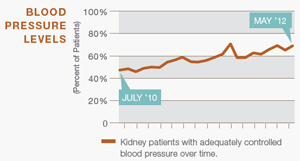

“Only half of all kidney transplant patients have blood pressure that’s controlled,” Hooper says. “There are 20 to 25 medications known to be effective at controlling blood pressure, so why are we not controlling it?”

He says the reasons are complicated. Patients are seen at various locations by different providers and caregivers often focus on immediate concerns such as avoiding organ rejection.

“It’s easy for longer term health issues to get lost in the mix,” Hooper says, “but ultimately it’s the cardiovascular care that’s allowing these kids to live longer or not.”

MONITORING KIDNEY PATIENTS |

|

|

New steps to ensure cholesterol and blood pressure checks at post-transplant visits are helping kids keep these levels under control. |

Building A Safety Net

So Hooper and his colleagues have built fail-safe measures into Cincinnati Children’s system.

New standards for outpatient care help assure that providers check for elevated blood pressure and cholesterol when transplant patients come back for checkups.

“Now, more than 90 percent of the time, blood pressure is being measured and documented according to guidelines at all locations,” he says.

Hooper and his team also developed “planned medical visits,” in which they review a patient’s records to plan for health-related issues that need extra attention.

“We look at things like, are they struggling to get to visits? Do they need help remembering to take their medications? Or are they ready to work on diet and exercise?” Hooper says.

“Before the clinic visit, we’ve assessed a behavior that might need changing and have identified who will work with the patient.”

The measures have been well received by providers, which has led to an upswing in capturing blood pressures and cholesterol — and in the number of patients experiencing better control of those factors.

Patients are also warming to the approach, but slowly, says Hooper.

“I’ve seen some kids respond well. Others just aren’t ready. In that case, we just work with them and wait for a time when they are ready. We explain that it’s not a sprint, it’s a marathon. Taking care of his health needs to be something a kid adopts for life."