How is Coarctation of the Aorta Treated?

In a critically ill newborn who comes into the hospital after the ductus arteriosus closes and there is a severe coarctation, the goals are to improve ventricular function and restore blood flow to the lower body. A continuous intravenous medication, prostaglandin (PGE-1), is used to open the ductus arteriosus. This allows blood flow to the body beyond the coarctation. Often other intravenous (IV) medicines may also be needed to help the function of the heart. Many babies need to be placed on a ventilator before surgery.

If the baby has symptoms of a coarctation, surgery is done on an urgent basis.

If there is a high suspicion of a coarctation prior to delivery, the PGE-1 medication can be started soon after birth to prevent the ductus arteriosus from closing. In this case, surgery would be done to repair the coarctation prior to discharge home from the hospital.

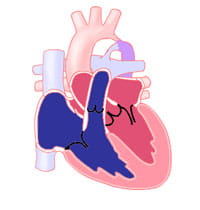

There are a few surgical techniques to repair coarctation. The most common repair involves resection (removal) of the narrowed area with anastomosis (reconnection) of the two ends to each other. Sometimes the removal of tissue must be extended further into the aortic arch if there is a longer piece of narrowing. In another method, the narrowing may be opened with a patch or a portion of an artery may be used as a flap to expand the area (called a subclavian flap aortoplasty).

To repair coarctation surgically, clamps must be placed on the aorta. This will quickly interrupt blood flow to areas supplied by blood vessels from the aorta. Complications of surgery include damage to organs such as the kidneys or the spinal cord, but these are not common in children.

Because older children may have minimal symptoms, coarctation repair is typically planned electively. Surgical repair is usually done with resection of the narrowed piece and end-to-end reconnection.

In older children who are closer to adult size, transcatheter therapy is the first-line therapy. It offers the ability to use a balloon or stent to dilate (make the area bigger) the area of narrowing without needing surgery. In children who are still growing, the placement of a stent means that additional catheterization procedures are likely to be needed in the future as the stents cannot grow with them.