What is an Interrupted Aortic Arch?

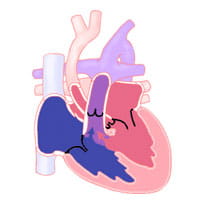

The aorta is the main blood vessel that carries oxygen-rich blood away from the heart to the organs of the body. After it leaves the heart, it first goes into the chest to give off blood vessels to the arms and head. Then, it turns downward. This path forms the typical candy cane structure of the normal arch. This leads toward the lower half of the body.

Interrupted aortic arch (IAA) means there is a missing portion of the aortic arch.The arch does not form a complete candy cane shape.

There are three types of interrupted aortic arch. They are grouped according to the area of the missing piece

- Type A: The interruption occurs just past the left subclavian artery. About 30% to 40% of infants with interrupted aortic arch have type A.

- Type B: The interruption occurs between the left carotid artery and the left subclavian artery. Type B is the most common form of interrupted aortic arch. It accounts for about 53% of reported cases.

- Type C: The interruption occurs between the innominate artery (an artery that comes from the aortic arch, towards the right side of the body) and the left carotid artery. Type C is the least common form of interrupted aortic arch. This occurs in about 4% of cases.

Interrupted aortic arch is thought to be a result of flawed development of the aortic arch system during the fifth to seventh week of fetal development. This defect is usually associated with a large ventricular septal defect (VSD). Patients with interrupted aortic arch (particularly those with type B) often have a genetic disorder called DiGeorge syndrome. In addition to interrupted aortic arch, patients with DiGeorge syndrome may have problems with low calcium, developmental delay, and immune system abnormalities.

Associated Problems

In patients with interrupted aortic arch, oxygen-rich blood from the left side of the heart is not able to reach all areas of the body. An infant with interrupted aortic arch must depend on another way to get blood flow to the lower body.

Normally, a fetus has an extra arterial connection called a ductus arteriosus. The ductus arteriosus is critical to survival in the womb. Shortly after birth, the ductus arteriosus usually closes. If the ductus arteriosus stays open, it is called a patent ductus arteriosus (PDA).

In a child with interrupted aortic arch, the PDA gives another way to get enough blood flow to the lower body.

While the ductus arteriosus is open, infants may not have noticeable symptoms. As the ductus arteriosus starts to close, the infant begins to show signs and symptoms of not having enough blood flow to the lower half of the body. The ductus arteriosus typically closes in the first one to two days of life. Not getting enough blood flow to the body may lead to severe symptoms. These may include shock and congestive heart failure.

If a ventricular septal defect is present, blood will be moved (shunted) from the left side to the right side of the heart. This shunting causes an increase in blood flow to the lungs. This leads to congestive heart failure as well.

Signs and Symptoms

Signs and symptoms of poor perfusion or congestive heart failure may develop when the ductus arteriosus begins to close.

The infant may develop tiredness, poor feeding, rapid breathing, fast heart rate or low oxygen levels. The oxygen levels are typically lower in the feet.

This condition can worsen and lead to shock. The infant will be pale, mottled and cool. The infant will likely have fewer wet diapers and poor pulses, particularly in the lower extremities.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of interrupted aortic arch may be suspected based on the symptoms the infant has. It is confirmed by an echocardiogram. Once the diagnosis is confirmed, treatment and surgical intervention are important.

This heart defect may also be diagnosed on fetal echocardiograms. Echocardiograms are an ultrasound that gives detailed information about the anatomy and function of the heart.

Early diagnosis of the defect allows for prompt intervention at the time of birth. Making the diagnosis before birth allows the obstetrical and fetal cardiology teams to plan the delivery so the infant is able to quickly receive the medications and attention they need.

Learn more about our Fetal Heart Program.

Treatment

Immediate treatment includes a prostaglandin infusion. Prostaglandin is a medicine that is given intravenously (IV). It keeps the ductus arteriosus open. This allows blood flow to the lower body until surgery is done to fix the interruption in the aortic arch.

Goals of treatment are to stabilize and support the infant until surgery happens. Treatment may include:

- Intubation (endotracheal or “breathing tube” placed in the airway)

- Diuretic therapy (water pills) to help the infant pee out the extra fluid

- Giving inotropic medications (to help improve the pumping action of the heart)

- Monitoring and correcting abnormal blood gases (carbon dioxide and oxygen levels in the blood) and electrolytes (potassium and calcium levels in the blood)

- Nutrition support

The goal of surgery is to reconnect the aortic arch to create a continuous "tube" and close the ventricular septal defect. Surgery is usually done quickly after the infant is stabilized (usually in the first few days of life).

Complications after interrupted aortic arch repair may include continued stenosis (narrowing) at the aortic repair site.

The aortic valve or the area below the valve are often small and may not grow. This can result in stenosis (narrowing) months or years after surgery. Sometimes these complications require another intervention, either surgery later in life or a cardiac catheterization procedure to open up areas of recurrent narrowing.

Surgery

Survival is not possible without surgery. Survival after complete repair of the aortic arch and ventricular septal defect in the newborn period is 90%.

Adult and Adolescent Management

Long-term follow up by the cardiologist to watch growth of the aortic valve region and the reconstructed aortic arch is important. Another surgery to address further problems with these areas may be needed in 10% to 20% of patients.

Any adult patient with a history of aortic arch stenosis will need lifelong care by an expert in congenital heart defects.

Learn more about the Adolescent and Adult Congenital Heart Disease Program.