What is Intestinal Atresia and Stenosis?

Intestinal atresia is a broad term used to describe a complete blockage or obstruction anywhere in the intestine. Stenosis refers to a partial obstruction that results in a narrowing of the opening (lumen) of the intestine. Though these conditions may involve any portion of the gastrointestinal tract, the small bowel is the most commonly affected portion.

The frequencies, symptoms and methods of diagnosis differ depending on where the blockage is. But children with all forms of intestinal atresia require surgery.

What are the Types of Intestinal Atresia?

Pyloric atresia

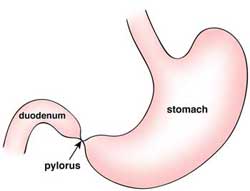

Pyloric atresia involves an obstruction at the pylorus, which is the passage linking the stomach and the first portion of the small intestine (duodenum). This is quite rare, and tends to run in families. Children vomit stomach contents, and because of the buildup of intestinal contents and gas, have a swollen (distended) upper abdomen. Abdominal X-rays reveal an air-filled stomach but no air in the remaining intestinal tract.

|

|

Pyloric Atresia |

Duodenal atresia

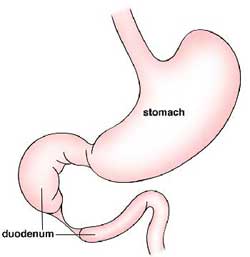

The duodenum is the first portion of the small intestine that receives contents emptied from the stomach. Duodenal atresia occurs in one out of every 2,500 live births. Half of the infants with this condition are born prematurely, and approximately two-thirds have associated abnormalities of the heart, genitourinary or intestinal tract. Nearly 40% have Down syndrome. Infants with duodenal atresia usually vomit within hours after birth, and may develop a distended abdomen. Abdominal X-rays show a large, dilated stomach and duodenum without gas in the remaining intestinal tract.

|

|

|

Duodenal Atresia - Example 1 |

Duodenal Atresia - Example 2 |

Jejunoileal atresia

Jejunoileal atresia involves an obstruction of the middle region (jejunum) or lower region (ileum) of the small intestine. The segment of intestine just before the obstruction becomes massively enlarged (dilated), limiting its ability to absorb nutrients and push its contents through the digestive tract. In 10% to 15% of infants with jejunoileal atresia, part of the intestine dies during fetal development. Many infants with this condition also have abnormalities of intestinal rotation and fixation. Cystic fibrosis is also an associated disorder and may seriously complicate the management of jejunoileal atresia. Infants with jejunoileal atresia should be screened for cystic fibrosis.

Cystic fibrosis is also an associated disorder and may seriously complicate the management of jejunoileal atresia. Infants with jejunoileal atresia should be screened for cystic fibrosis.

|

|

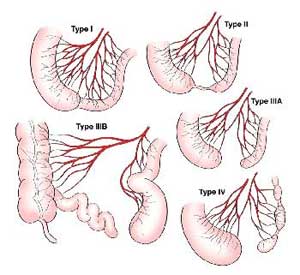

Four subtypes of jejunoileal atresia |

Types of jejunoileal atresia:

- Atresia type I — The blockage is created by a membrane (web) present on the inner part of the intestine. The intestine usually develops to a normal length.

- Atresia type II — The dilated intestine stops as a blind end. It is connected to a smaller segment of the intestine by a fibrous scar. The intestine develops to a normal length.

- Atresia types IIIa and IIIb — The blind ends of intestine are separated by a defect in the intestinal blood supply. This often leads to a significantly shortened intestinal length that may result in long-term nutritional deficiencies or short bowel syndrome.

- Atresia type IV — Multiple regions of obstruction exist. This may result in a very short length of useful intestine.

Infants with jejunoileal atresia, regardless of the subtype, usually vomit green bile within the first 24 hours of life. However, those with obstructions farther down in the intestine may not vomit until two to three days later. Infants often develop a swollen (distended) abdomen and may not have a bowel movement (as is normally expected) during the first day of life. Given the age of the patient and the symptoms, it can usually be diagnosed with an abdominal X-ray.

Colonic Atresia

This rare form accounts for less than 15% of all intestinal atresias. The bowel becomes massively enlarged (dilated), and patients develop signs and symptoms similar to those associated with jejunoileal atresia. Colonic atresia may occur with small bowel atresia, Hirschsprung's disease or gastroschisis. The diagnosis is confirmed by an abdominal X-ray along with an X-ray contrast enema.

How is Intestinal Atresia and Stenosis Diagnosed?

Intestinal obstructions are increasingly being identified through prenatal ultrasounds. This imaging may show excess amniotic fluid (polyhydramnios) when the intestine doesn’t properly absorb the fluid.

If your doctor suspects intestinal atresia or stenosis after birth, your infant will have the following diagnostic procedures after being stabilized:

- Abdominal X-ray: In most cases, this can establish a diagnosis.

- Contrast enema This is a procedure that examines the rectum, large intestine and lower part of the small intestine. An X-ray contrast agent is given into the rectum as an enema; this coats the inside of the intestines, allowing them to be seen on an X-ray. The abdominal X-ray may show the width (caliber) of the bowel, narrowed areas (strictures), obstructions and other problems.

- Upper GI series: This procedure examines the organs of the upper part of the digestive system. It is helpful when there is an upper intestinal obstruction (pyloric or duodenal atresia). A liquid contrast solution, which shows up well on X-rays, is given by mouth or through a small tube placed through the mouth or nose into the stomach. X-rays are then taken to evaluate the digestive organs.

- Abdominal ultrasound: Ultrasonography is an imaging technique used to view internal organs as they work, and to check blood flow through various vessels. Gel is applied to the abdomen, and a special wand called a transducer is placed on the skin. The transducer sends sound waves into the body that bounce off organs and return to the ultrasound machine, producing an image on the monitor. A picture or videotape of the test is also made so it can be reviewed later.

Due to the high percentage of infants born with intestinal atresia who also have associated, life-threatening abnormalities, echocardiography and other imaging studies of the cardiac and renal regions may also be performed after the infant is stabilized.

How is Intestinal Atresia and Stenosis Treated?

Children with intestinal atresia and stenosis require an operation, and the exact type of operation depends on where the obstruction is.

Before the operation, all babies must be stabilized. The excess intestinal contents and gas that contribute to abdominal swelling (distention) are removed through a tube that is placed into the stomach through the mouth or nose. Removing air and fluid from the intestinal tract can prevent vomiting and aspiration (choking), and reduce the risk of bowel perforation. It also gives babies some comfort as abdominal swelling is relieved. Intravenous (IV) fluids are given to replace vital electrolytes (minerals and salts in the bloodstream and body) and fluid that has been lost through vomiting. Once the baby is stabilized, surgery is performed to repair the obstruction.

Pyloric Atresia

The pyloric obstruction is opened and the stomach passageway is repaired. The success rate of this operation is excellent. Length of hospital stay is generally between one to three weeks. But, as in all types of intestinal atresia, the hospital stay is much longer for premature infants.

Duodenal atresia and stenosis

Duodenal atresia and stenosis are managed by connecting the blocked segment of duodenum to the portion of duodenum just past the obstruction. Additionally, a tube may be temporarily placed through a surgical opening in the abdominal wall (gastrostomy) to drain the stomach and protect the airway. This tube can also be used for feeding if needed. Parents can expect their child to remain in the hospital from one to several weeks, until the child can get enough nutrition from their diet.

Parents can expect their child to remain in the hospital from one to several weeks, until the child's diet is sufficient to permit adequate nutrition.

Jejunoileal atresia and stenosis

With jejunoileal atresia, the type of surgery depends on the type of atresia, the amount of intestine present and the degree of intestinal dilation. The most common operation removes the blind intestinal segments, and the remaining ends are closed with sutures. Similarly, a narrowed (stenosed) segment of the intestine can be removed and the bowel sewn together.

Colonic atresia

Babies with colonic atresia may have the enlarged (dilated) colon removed and a temporary colostomy. Less frequently, the ends of colon are sewn together.

Infants With Intestinal Atresia and Stenosis

Babies with atresia are managed with a nasogastric tube that is left in place until their bowel function returns. This may vary from a few days to several weeks. During the period of bowel inactivity, nutrition is provided intravenously (through IV). Once the intestinal function is normalized, nutrition is provided orally or through a feeding tube.

What is the Long-term Outlook for Intestinal Atresia and Stenosis?

Children who have surgery for intestinal atresia need regular follow up to ensure adequate growth, development and nutrition.

How babies progress mostly depends on whether there is an associated abnormality and whether or not the baby is left with enough intestine. In general, most babies do well. Complications after surgery are rare, but may occur. Soon after surgery, intestinal contents may leak at the suture line where the ends of the bowel were sewn together. This may cause an infection within the abdominal cavity and require additional surgery. Complications that may later occur include malabsorption syndromes, functional obstruction due to an enlarged and paralyzed segment of intestine, or short bowel/short gut syndrome.