From Dish to Discovery: Our Scientists Grow Miniature Intestines to Transform the Future of Medicine

“The future of medicine is literally right here in my hands,” says Michael Helmrath, MD, carefully holding a petri dish, his eyes alight. “In here is an intestinal organoid — a fully functioning miniature human intestine. And it could transform everything we know about pediatric medicine.”

As the surgical director of the Intestinal Rehabilitation program within the Colorectal Center at Cincinnati Children’s, Dr. Helmrath cares for babies and young children with a wide variety of intestinal disorders. He’s devoted his career—both clinically and in research—to finding better treatments for these kids.

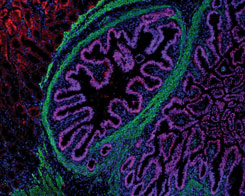

The path to creating these complex, functioning intestinal organoids began in 2010 at Cincinnati Children’s, when Jim Wells, PhD, and his team of researchers created the first miniature intestines. It was a groundbreaking discovery, but the tiny guts lacked nerves, which they needed to be fully functioning. Dr. Wells turned to Dr. Helmrath and his laboratory for clinical insight. And in 2016, this close-knit, cross-disciplinary team took the next step: The organoids began to grow nerve cells.

It was an unprecedented breakthrough for the researchers. “For the first time, we can take any patient’s cells and grow a miniature version of their intestines,” Dr. Helmrath explains. “And that puts us one step closer to understanding how human intestinal disorders occur.”

Our Connection to the World

A good portion of our interactions with the world around us involve our guts, from eating and drinking to taking medication. Moreover, research is showing us that our intestines are where our immune system develops and where allergies and autoimmune diseases begin.

“These organoids open up an entire world of research possibilities,” says Dr. Helmrath, shifting in his chair, practically vibrating with excitement. “We’re going to learn more about human disease than we have ever been able to do before.”

Disease research is just the beginning of the organoid’s potential uses. Because they work just like the intestines inside a human body, they can be used to test new medications for toxicity before clinical trials. Nutritional health studies, food allergy research and more could all use these miniature intestines to advance knowledge and refine treatments.

For instance, organoids could help researchers and doctors discover how to better care for patients with cystic fibrosis (CF), a disease that causes thick mucus to build up in the lungs and intestines. Kids with CF have trouble getting adequate nutrition because the disease interferes with their bodies’ ability to digest food.

“Studying organoids created from cells from patients with CF could help us discover better treatments to get kids the nutrition they need,” says Dr. Helmrath.

Early studies will help researchers find more effective, more personalized treatments for their patients. Dr. Helmrath says, “This is why I’m so excited by this technology—it has tremendous potential to give us answers that will immeasurably help kids’ health.”

Bridging Funding Gaps

Despite its incredible potential to transform medicine and save lives, these first research steps rely on donor support.

“Research requires us to start with answering basic questions before we get to the big, innovative steps,” Dr. Helmrath explains. “The catch is, grant-making organizations like the National Institutes of Health only fund the larger studies that happen after those first, smaller studies.”

These funding gaps can doom research before it ever starts, which is why donor support is vital to making innovation happen.

In 2016, inspired by the potential of the tiny intestines, the Farmer family gave a lead gift to advance their initial studies. “After talking with Dr. Helmrath and hearing his passion for this research to help children, we wanted to help them get their work to the next level,” says Amy F. Joseph, trustee of the Farmer Family Foundation. “The fact that this visionary research is at Cincinnati Children’s sealed the deal for us—we’re proud of the hospital’s position as a growing national leader.”

Creating the Future Together

From donor to doctor, from researcher to patient, everyone plays a role in making research advancements like intestinal organoids a reality. We believe that we have the power to save lives through collaboration.

“This work is absolutely changing the outcome, giving us the chance to tackle complex intestinal disorders like never before,” says Dr. Helmrath, leaning forward, his words emphatic with excitement. “Because of donors, this research will get to patients quicker, improving the care we give to kids facing everything from Crohn’s disease to intestinal cancers.”

While organoid research is still in its earliest stages, its biggest impact may be in the hope it represents. This breakthrough could lead to a future where a patient’s own cells could be used to grow healthy intestinal tissue to cure a chronic condition.

When we get to that stage, it will be not only because of researchers and clinicians, but because of the commitment of our donors to a future where all kids have the potential to be healthy and vibrant.